How to Design a Value-Based Sale that Drives Business Impact

TL;DR

Have you ever been told to “sell value” by a sales leader?

If so, you know it’s a throwaway piece of advice that seems helpful. But it’s like telling a runner, “Just run faster!” I mean…. yeah, sure. I’d love to. But how?

“Value” is one of those squishy topics nobody defines in a specific, concrete way.

Send more eBooks? Be more “helpful?” What, exactly, is value?

What “Selling Value” Actually Means

Here’s a simple but specific definition of value:

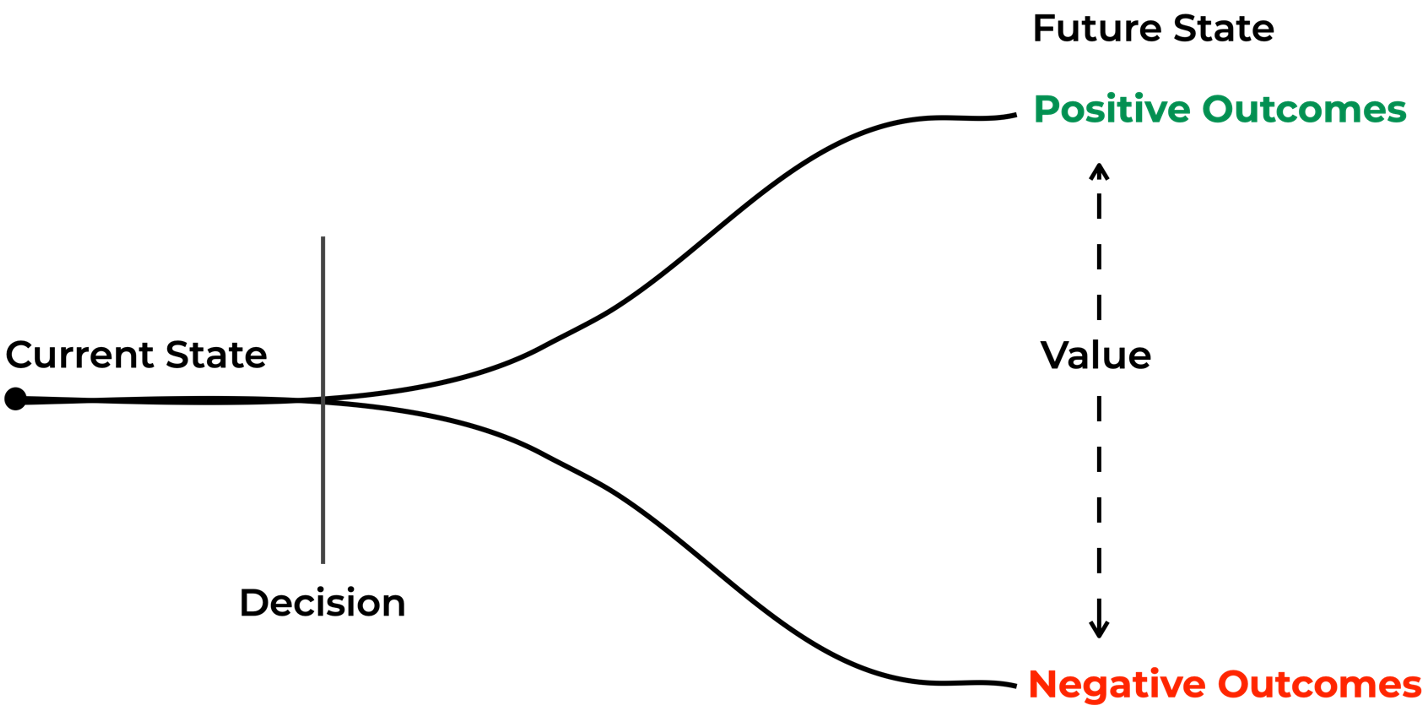

Value = Positive Outcomes — Negative Outcomes

It’s the space between two potential futures. One that’s desirable. One that’s not.

When a customer faces a problem, they can either choose to move toward:

- Negative Outcomes: The cost of a problem if it's left unsolved.

- Positive Outcomes: A payoff that's unlocked by making a change.

Which means value increases when:

- The cost of the problem you'll avoid increases.

- The return from a new project you'll rollout increases.

Most sellers have heard some of this described as "quantify pain." It’s a good start.

But you can also take that a few steps further to dial your “value story” up to 100.

Two Principles for Crafting a “Value Story”

Most people tend to believe that a solid business case is all about the numbers. Showing an ROI that's too big to say no to.

But a true business case is built around an internal narrative, a storyline, that puts those numbers in the context of:

- Executive-level priorities leadership is already sold on.

- Strategic projects CFO's will invest in.

Our brains are wired to understand the narrative structure, which is built on two principles:

- A Consistent Pattern: Joseph Campbell's The Hero's Journey showed how every memorable story is designed around the exact same pattern.

An interesting character encounters a problem, which forces them to choose a path forward. That choice will lead to one of two endings. Comedy, or tragedy.

- Contrast: Our brains ❤️ contrast. We can’t see “value” in isolation. Only when things stand in comparison to each other. Which is why a good story highlights both:

- Comedy: Positive outcomes we get to live out.

- Tragedy: Negative outcomes we just avoided.

It's easier to make a choice between black and white than shades of gray.

You'll apply both of these principles to the storyline inside a business case — a type of Value Story, in other words — when you:

- Move from costs to consequences.

The cost of inaction (COI) is a 1st-order effect. But prospects need to connect this to the 2nd- and 3rd-order effects, too. The negative outcomes, in other words. For example:

1st Level (COI): “We lost $2M ARR we should’ve won this quarter.”

↓

2nd Level: “Winning less customers with the same sales & marketing spend inflated our cost to acquire customers (CAC).”

↓

3rd Level: “Our GTM Efficiency is pretty ugly right now, yet we’re about to fundraise in a tough capital market. Hello, dilution.”

- Flip those consequences upside down to find the payoff.

Like we said, value = the positive outcomes you enable (—) the negative outcomes created by the current state.

So, if you measure the problem with ARR, CAC, and GTM Efficiency, the payoff should be measured with those exact same metrics.

Building a Bridge: Sell an “Approach” Before a Product

Your job as a seller is to build a bridge between the customer's current and future states. To show them the path that avoids tragedy, and ends in comedy.

So how do you that, practically speaking? You make a strategic recommendation to guide the customer’s approach to creating change.

The approach is how you solve a problem. Not who or what solves it.

Which is what the majority of sellers miss. They hear a problem, they show their solution. While completely forgetting to eliminate project risk (choosing to take an altogether different path), and focusing too narrowly on product risk (walking a specific path with someone else).

It's easy to miss because the approach is neutral framing. It's vendor agnostic.

So before you speak to a specific set of features, confirm everyone’s aligned on the higher-order questions of:

- What’s the right value driver to focus on?

- What must be true about how we impact that driver?

I say again. The approach isn't “buy XYZ software.”

Instead, it’s focused on a core shift, practice, or project that impacts a specific value driver.

Less, “use our content automation." More, “shift the mix of leads from paid to organic sources.”

Influencing a Newly-Hired CRO’s Approach & Impacting Value Drivers

Take a newly hired CRO as an example.

Let's say her company just raised a Series B. Now, she's got to deliver on the happy ending they promised investors. So the CRO will ask herself, “What’s my biggest revenue opportunity?”

Is it acquiring new logos? Boosting net revenue retention (NRR)?

Let’s say it’s NRR. Investors were talking about that a lot. But does she...

- ...hire more AM's for the enterprise segment?

- ...find untapped cross-sells for SMB's?

- ...take an altogether different path?

There are lots of different value drivers she can focus on.

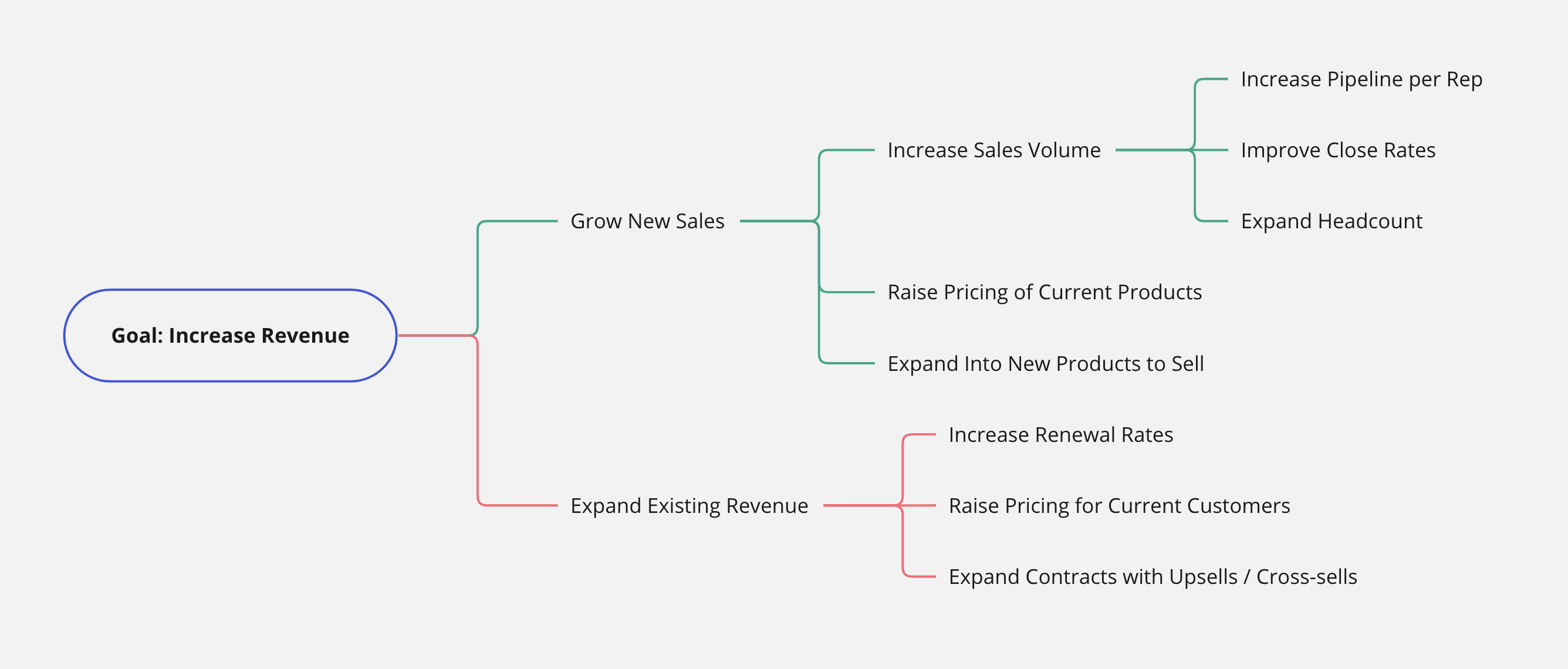

In fact, if you look at this example “driver tree”, you’ll notice that when you sell to executives who own very high-level metrics, they have lots of choices, trade-offs, and competing priorities.

You can “drive revenue” in a lot of ways:

If you haven't seen a driver tree before, here's a quick definition:

A way to map the value created by a company, by linking outcomes to a series of inputs. On the left side, list a target metric you’d like to impact. On the right, you'll see what "drives" that metric.

Okay, so, this CRO’s got to pick her priority today, which will affect buying decisions tomorrow.

Now, let's suppose you sell a sales intelligence platform that helps generate leads. You see this CRO was just hired. She just raised a Series B. Perfect timing to reach out, right?

Well, if the CRO’s thesis is that a singular focus on NRR is best — so she’s entirely focused on expanding revenue from the customers who already love them — you have one of two options while designing your deal:

- Align with her thesis.

Let’s say you can give her data on customers who recently changed jobs, and could champion her product at their new company.

- Reshape her thesis.

How long can she afford to focus on NRR, without landing new logos? Aren’t the seeds for NRR sown early, during the new sales and onboarding process?

If there’s no logical bridge between her priority and your product—an approach that she’s aligned with—it’s not time to sell your product. There's still more to the story.

Enable Your Champions With this Value Story Framework

So, back to our first point.

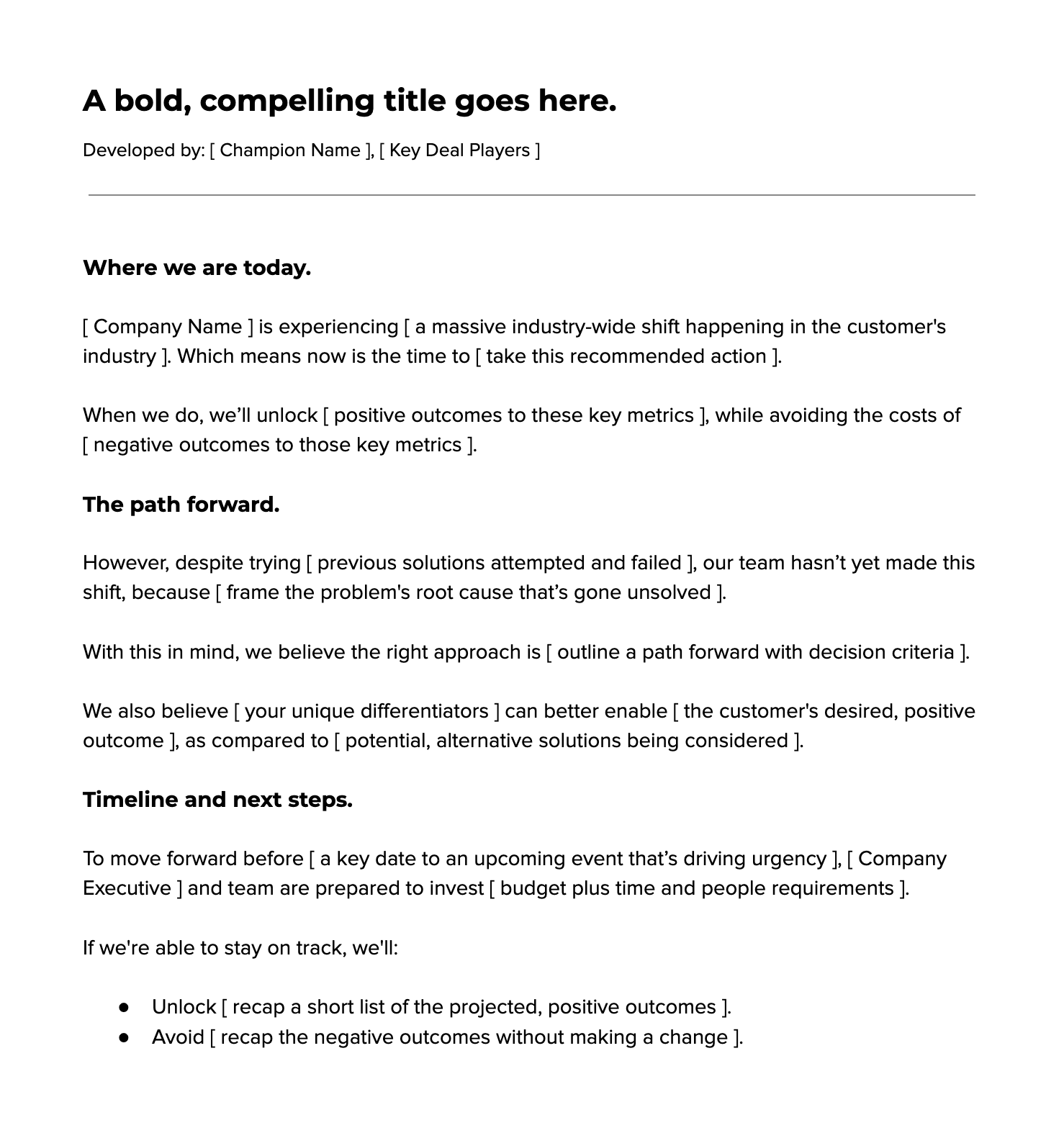

Whenever you're told to "sell value," here's how to actually do that:

- Setting: understand where your customer is today, and where they want to go tomorrow.

- Choice: map the customer's business using a driver tree, and settle on the right approach.

- Ending: measure the problem, and flip it upside down to create contrast to a clear payoff.

Once you've outlined these three elements, use this "Mad Libs" style framework and plug in your buyers' own words from your sales meetings.

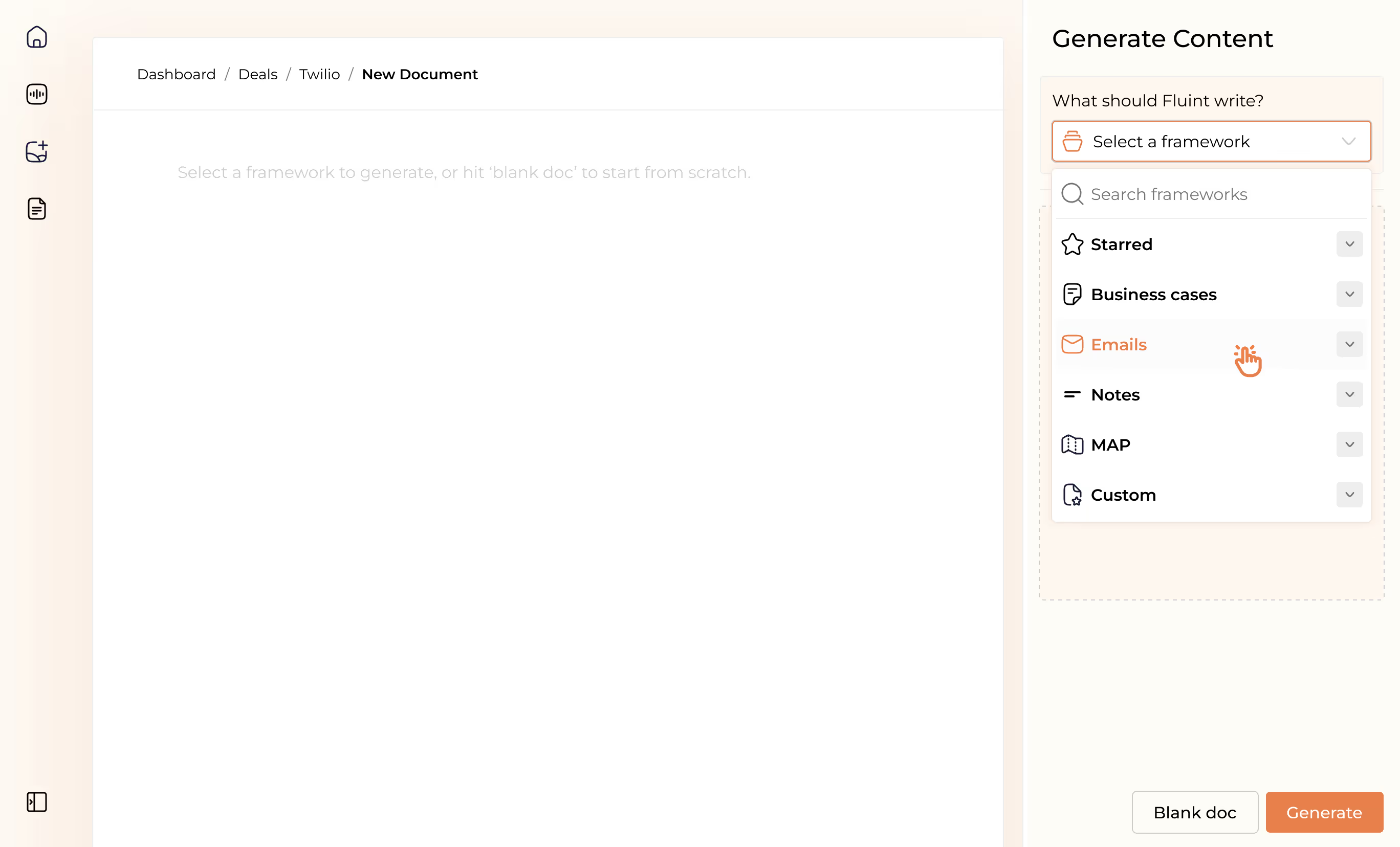

Or, just have Fluint write the first draft for you.

It'll help you craft a Value Story with your champions, to guide their internal buying convo's.

FAQ's on:

Why stop now?

You’re on a roll. Keep reading related write-up’s:

Draft with one click, go from DIY, to done-with-you AI

Get an executive-ready business case in seconds, built with your buyer's words and our AI.

Meet the sellers simplifying complex deals

Loved by top performers from 500+ companies with over $250M in closed-won revenue, across 19,900 deals managed with Fluint

Now getting more call transcripts into the tool so I can do more of that 1-click goodness.

The buying team literally skipped entire steps in the decision process after seeing our champion lay out the value for them.

Which is what Fluint lets me do: enable my champions, by making it easy for them to sell what matters to them and impacts their role.