How to Manage Up: 10 Steps to Become a Standout Account Executive

TL;DR

Early in a seller’s career, most reps believe sales organizations are meritocracies.

That good things like promotions and pay bumps, trust and freedom, go to those who generate the most revenue. That’s more true in sales than in most fields. But it’s still only half true.

In reality, sales organizations are blends of meritocracy and bureaucracy.

Sales organizations build “scaffolding” to help them scale up. Things like management hierarchies. Internal reporting systems. Standard procedures. Aka, all sorts of bureaucracy.

This creates the need to manage up.

If you want to keep your career and commission as an individual contributor. Or you’re interested in making the move to management. Learning to manage up (bureaucracy) — combined with closing revenue (meritocracy) — is how you’ll control your future, earnings, and work-life quality.

The Two Keys to Managing Up

The two steps to successfully managing up are:

- Create internal allies who hold influence, and will advocate for you.

- Enable these allies with a compelling narrative about your performance.

This is done through 1:1 conversations, team meetings, and written materials.

All with the goal of shaping decisions being made about you, without you.

The conversations that happen about your career, when you’re not in the room.

Sound familiar?

If you’ve read any other posts on this blog, you know I write about two main ideas:

- Buyers (not sellers) close deals when sales reps aren’t in the room.

- Sales is about creating champions, and crafting internal communications.

Which means managing up isn’t about acquiring a whole separate set of skills.

It’s about repurposing the same skills high-performing reps use to generate revenue (meritocracy), to navigate your own organization (bureaucracy).

If you can help your buyers navigate the complexity of their company, to shape the outcome of a major purchasing decision, it’s time to put these same strategies to work for yourself.

Here’s how.

1/ Write out your pipeline updates in narrative form.

If you don’t create the narrative, someone else will. When this happens, it’s far more challenging to shift an existing narrative someone that else created.

Start by sending out a weekly pipeline update to your direct manager. Share it in a consistent format, that’s easy for them to forward on when needed.

Here’s a framework you can build from:

2/ Talk in terms of scenarios and dependencies.

Nothing kills your reputation more quickly than deal slippage. Consistently calling your shot… only to miss the mark. Time after time.

So instead of saying, “I’ll close $X” this quarter,” the framework above uses three scenarios:

- Worst Case. What you’re proactively defending against. Label specific risks here.

- Base Case. This is your most likely scenario, contingent on a few reasonable assumptions.

- Best Case. Your 20 revenue if a few, major deals or wild card assumptions come through.

3/ Surface bad news early and often.

I like Charles Muhlbauer’s saying, “Bad news can’t wait.”

This is one of the most common, yet costly, mistakes I see young sellers make. They “shield” their manager from bad news. Which robs managers of the decision to either:

- Intervene and do something about the bad news.

- Get ahead of it by sharing with others.

- Save it for later.

Let your manager make that call. Don’t make it for them.

4/ Focus your 1:1 time on “high-leverage” requests.

If you’ve been doing all of the above, now, your typical 1:1 agenda is freed up.

You’ve moved past the routine items, and can focus on higher-quality conversations like:

- New project ideas you’d like to own and run with.

- Requests for more/new/different resources.

- Key account strategies.

By the way, you should use some type of shared doc to track commitments from these conversations, and your progress against them.

If a past commitment is important enough, but wasn’t completed by your manager on time, use some of your 1:1 time for it. Just say:

I know you have a lot on your plate, and I feel like < commitment > is important enough that it’s worth taking 5 minutes to do it together, now.

Are you open to spending a few minutes working heads down on this right now?

5/ It’s not what you’re asking. It’s how you’re asking.

If you have an important and/or urgent ask to make, focus on how you make it.

For example, when I wanted to ask one of my past CEO’s for the resources to build up an enterprise sales team, that big ask was spread into many smaller asks over 6-9 months:

- Can I spend 20% of the team’s time on landing larger accounts?

- Can we invest in this product change, to land this first enterprise account?

- Can we invest in more dedicated, enterprise CSM’s to bring on even more accounts?

And so on. Also, make sure to communicate in the way your manager uniquely listens.

With some people, I’d go into in the office for an hourlong meeting and start with small talk. With others, I’d keep my questions short and punchy, shared in a 30 minute phone call.

6/ Anticipate your manager’s needs to proactively deliver.

There are two pieces to this one.

The first is knowing your manager’s needs.

We tend to assume our biggest priorities are our manager’s biggest priorities. However, if you:

- Learn what questions your manager’s asked, you’ll know what questions they’ll ask you.

- Learn their manager’s big priorities, you’ll know what your manager’s big priorities are.

But in all likelihood, your manager’s priorities are constantly shifting. Which means:

- You’ll be front-of-mind at times. Say you’re selling the first logos in a new, strategic vertical that’s key for the whole company. Be proactive, and over-communicate in these seasons.

- You’ll be out-of-mind at times. That’s fine. It’s okay to go heads down, and allow them some space during these seasons.

Finally, deliver two steps ahead on their priorities.

If you’re asked for an update on A, deliver A, but also communicate about "B and C."

For example, let’s say you’re asked for an update on that new, strategic vertical.

"How’s the pipeline looking?" Your manager is asking about "A" here.

They need to tell Customer Success what accounts to expect and when ("A"). In this case, don’t stop at sharing the revenue or logo forecast. Share what special exceptions these prospects are requesting ("B"), that are going to create extra time and staff dependencies ("C").

7/ Think like a VP: cross-functionally.

Related to this last point, the more your career advances, the more you’ll find yourself working across department lines. It’s the natural trajectory of career growth.

If you're working on leveling up, go ahead and get started. Help someone outside your team.

For example, as an Account Executive, you can help:

- Marketing — create a list of common concerns with phrases that address them, to start weaving this into top-funnel content.

- Product — keep a spreadsheet with how often you hear certain feature requests, and ask prospects to rate them by impact.

- Success — write out a 90-day plan for onboarding a big, soon-to-close account and ask a CSM's input on it, to ensure the customer has a great experience.

- Sales — help your own team by documenting a process that's unique to you, and one you do really well, to share it with others.

It's hard to not be promoted when you're already doing a job that's bigger than your title.

8/ Clarify your personal goals. Carve out a path together.

Nothing is worse than expecting a promotion, pay bump, or other perk — but not getting one — because you were producing the wrong type of evidence.

Different sales leaders rely on different signals to identify top performers.

Some value predictably. People who hit the number they say they’ll hit — even if their production is lower than others. Other leaders prioritize team contributors. Or peer reviews.

Whatever the evidence is, align on it by sharing:

A good year for me will end with < perk / benefit / promotion >, which is part of my overall goal to < longer-term career goal >.

So, I’m wondering, what will you and leadership look at, to determine if I’m in a good position for this?

To state the obvious, if you haven’t told your manager what, exactly, you’re working towards, they’ll have a hard time advocating for you.

9/ Gut-check alignment, and ask for direct feedback.

Giving straight-up feedback is hard. Most managers don’t like to do it. So giving them the permission to be direct with you is a gift, for both of you.

Do this by asking questions like:

Related to our discussion on < shared goal >, what do I still need to improve on here?

When was the last time you were asked for an update about my work, but didn’t have the information you needed from me at the ready?

On a scale of 1 – 10, how aligned do you feel my work is with the team’s goals right now?

10/ Be consistent.

The more practices from this list you follow — and the more consistently you follow them — the stronger the case for you becomes. The thing is:

- 30% of reps are doing one of these practices

- 20% of reps are doing two of them

- 10% of reps are doing three to four

- 1% of reps do all of them.

How many will you follow this month? Will you follow them again next month?

In summary, notice the two common threads tying all of these practices together:

- You’re turning your own colleagues into champions who will advocate for you.

- You’re building a strong narrative backed with evidence for them to share.

Which makes managing up just another way to apply your sales skills. Inside your own company.

FAQ's on:

Why stop now?

You’re on a roll. Keep reading related write-up’s:

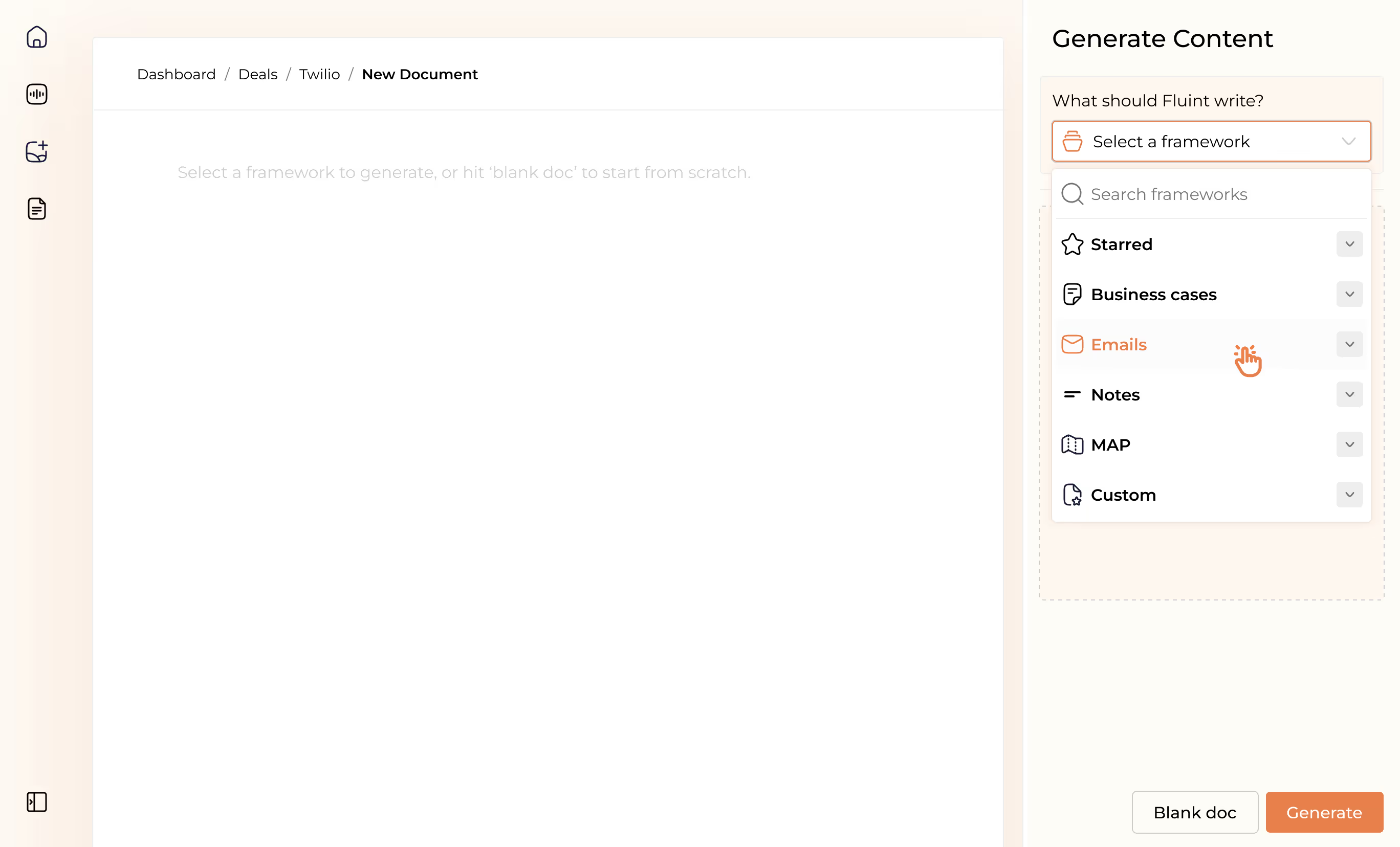

Draft with one click, go from DIY, to done-with-you AI

Get an executive-ready business case in seconds, built with your buyer's words and our AI.

Meet the sellers simplifying complex deals

Loved by top performers from 500+ companies with over $250M in closed-won revenue, across 19,900 deals managed with Fluint

Now getting more call transcripts into the tool so I can do more of that 1-click goodness.

The buying team literally skipped entire steps in the decision process after seeing our champion lay out the value for them.

Which is what Fluint lets me do: enable my champions, by making it easy for them to sell what matters to them and impacts their role.