The “Hardwired” Enterprise Proof of Concept Framework: Land & Expand All-in-One

TL;DR

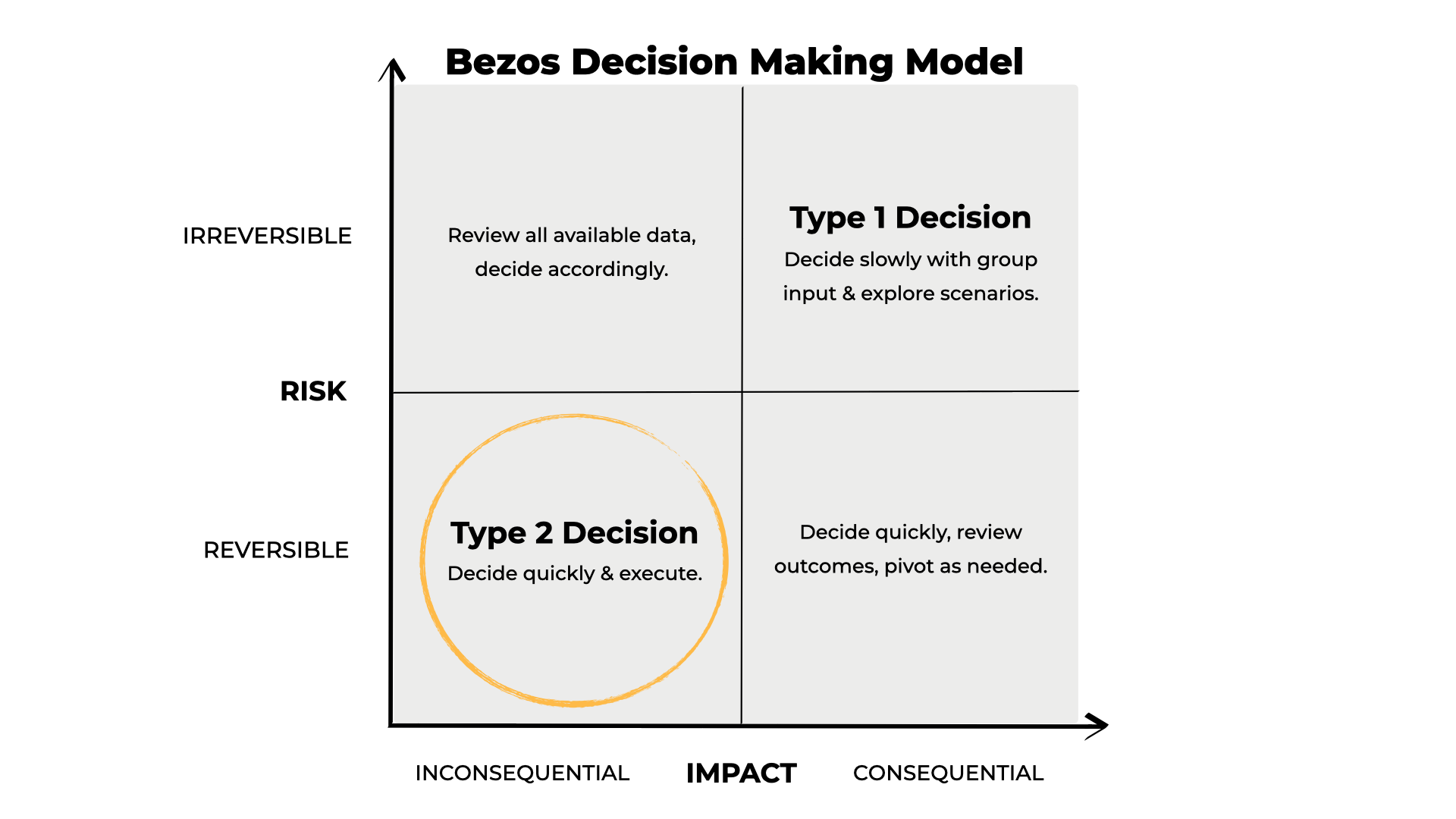

Jeff Bezos described his decision making model of “one-way” and “two-way” doors in a 1997 letter to shareholders:

Some decisions are consequential and irreversible – one-way doors – and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation. If you walk through and don’t like what you see on the other side, you can’t get back to where you were before. We can call these Type 1 decisions.

He goes on to say:

But most decisions aren’t like that – they are changeable, reversible – they’re two-way doors. If you’ve made a suboptimal Type 2 decision, you don’t have to live with the consequences. You can reopen the door and go back through. Type 2 decisions can and should be made quickly by high judgment individuals or small groups.

He was putting language behind the way most executives think. They spend a lot of time analyzing big decisions. Think of Bezos’ model like this:

Here’s the rub for sellers:

- The larger the deal, the more irreversible & consequential it seems.

- This makes for long cycles, with lots of research and evaluation.

Coupled with all the bureaucracy in big companies, it’s like trying to drive a deal forward with the parking brake on. Momentum stalls, warning lights flash.

Bezos agrees:

As organizations get larger, there seems to be a tendency to use the heavy-weight Type 1 decision-making process on most decisions, including many Type 2 decisions. The end result of this is slowness, unthoughtful risk aversion, failure to experiment sufficiently, and consequently diminished invention. We’ll have to figure out how to fight that tendency.

This means your job is to enable a fast yet thoughtful decision, by turning what buyers see as a Type 1 decision, into a Type 2 decision.

A concrete way to do this is with creative contract structures. Here’s an example of how Sir Richard Branson created a “reversible” contract:

When we launched Virgin Atlantic I made a deal with Boeing that we could hand the plane back in a year's time if the airline didn't get off the ground. Thankfully, we never had to. But if the things hadn't worked out, I could have walked back through the door.

Basically, his contract could be reversed if he didn't get his airline "off the ground."

A great deal for Virgin Galactic. Fraught with issues for sales reps — like clawbacks if a deal is reversed. So here’s a better alternative we'll unpack:

A focus on expansion terms instead of extinction terms.

This post will show you a non-traditional proof-of-concept (POC) framework that takes risk off the table, leads to fast expansion deals, and helps buyers see your deal as a “Type 2” decision.

Why This POC Framework is Crazy Effective

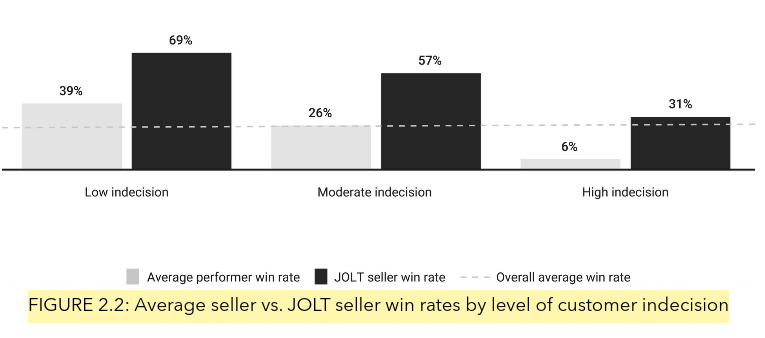

The JOLT Effect recently put data behind why this process has been crazy effective for me and my teams. JOLT sellers:

- (J)udge Indecision: an ability to buy must be paired with an ability to decide.

- (O)ffer a Recommendation: Buyers who are indecisive need guidance. Not choices.

- (L)imit the Exploration: Shared more information can become counterproductive.

- (T)ake Risk Off the Table: The cost of inaction needs to be measured. But to move forward, go beyond costs by removing downside risk.

Here’s the difference this approach makes:

If the JOLT framework is a conceptual wrapper, think of this process as the candy inside. A way to sweeten your deal, and get rid of risk and regret’s bitter aftertaste.

The typical POC is just a paid trial.

Which makes it a losing strategy. The belief is that buyers need more information, more access, and more experience in the product to help them decide.

That product access often comes with:

- Way too broad of a scope

- An ambiguous timeline

- No defined goals

Just as the JOLT framework shows, this is the opposite of what you want. Instead of “limiting exploration,” you’re opening Pandora’s Box.

Plus, it does little to de-risk a decision. In fact, it often highlights just how different life will be with your product, which isn’t always good. Lots of change = uncertainty. Uncertainty = fear.

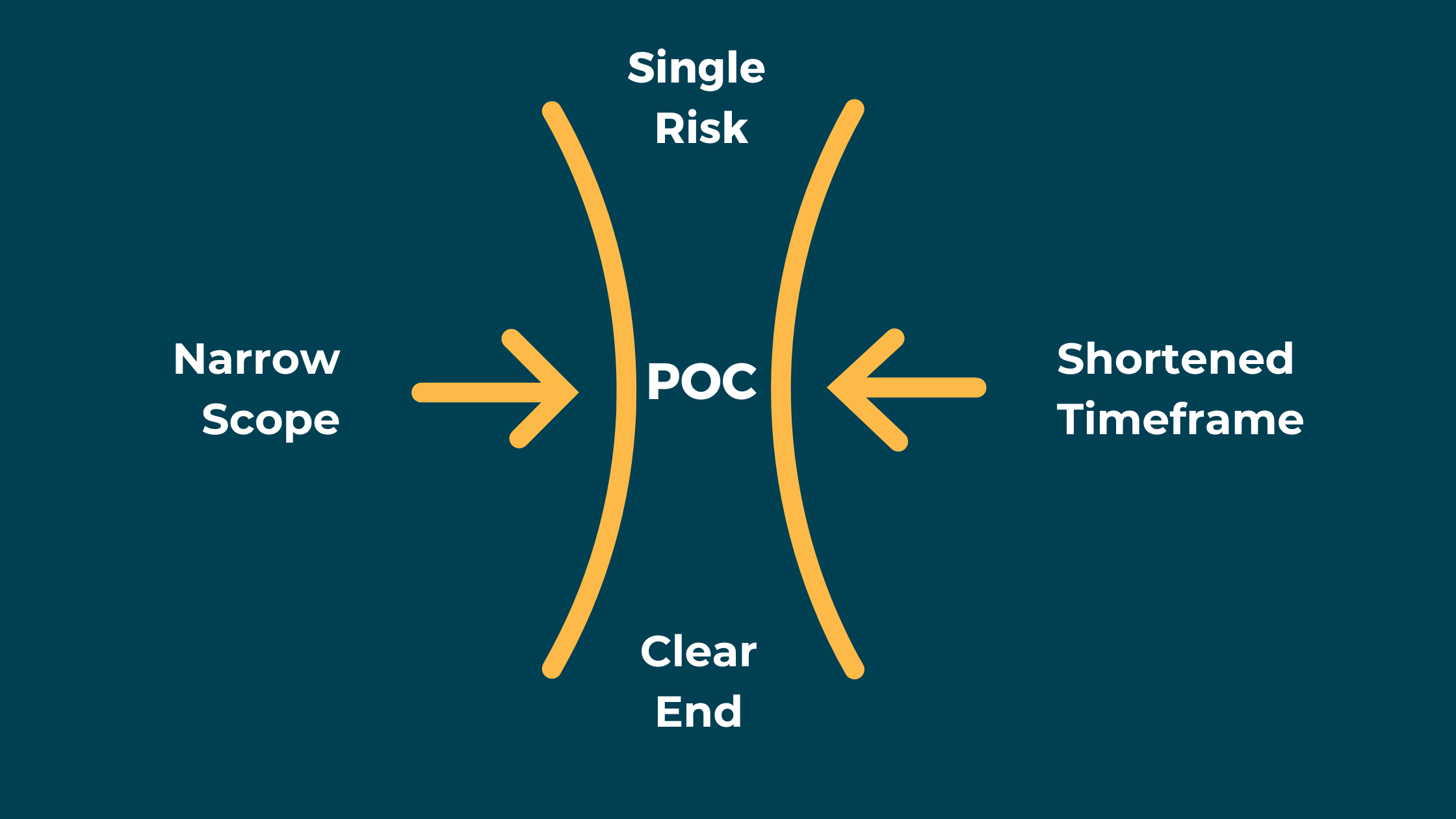

The Framework for Winning POC's

Every POC has 5 basic elements to it:

- Scope

- Timeline

- Hypothesis

- Measurables

- Next Steps

Effective POC’s combine these elements into a structure that delivers:

- The least amount of activity

- Over the shortest period of time

- Focused on a single big uncertainty

- To lower perceived risk and barriers to change

- And end with a clear go/no-go condition.

1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 = more revenue, in less time.

Let’s break down each part of this framework.

(1 + 2) POC's Should Require Minimal Effort

Short and fast POCs are best. Not just for your sales cycle, they’re an easier initial ask for your buyers. So it’s worth highlighting that I’m not using the term “Pilot” here.

Pilots and POC’s aren’t the same thing:

- POC’s strip out 80% of a product’s scope to focus on a small subset of activities.

- Pilots are a full product rollout, but only to a subset of customers or users in a test market.

Most POC’s are over-engineered. There’s too much activity. You’ll scale them down when you force constraints into the equation. With a timeline, for example, which can lead you to ask:

What must be true to do this in less than < timeline, e.g. 2 weeks >?

You might use dummy data instead of live customer data, and cut out all “ETL” activities.

How you’ll arrive at the least amount of activity over the shortest period of time is also linked to your hypothesis ↓

(3 + 4) POCs Should be Narrow & Focused

The major reframe here is shifting from viewing POC’s as a trial, to a rapid, contained experiment that’s based on a specific hypothesis. This is literally in the name. Proof of concept. But it’s often skipped over.

- Most POCs start with the product. “What features should we include?”

- This process starts with the customer, by asking, “Why haven’t they changed already?”

This is an actual question you should ask your champions, by the way. Then:

- Continue asking the full buying team until you find a pattern.

- Create consensus on a single perceived risk driving the indecision.

- Develop an experiment to prove a hypothesis, focused on that risk.

This approach lets you conduct 20% of the trial activity to dispel 80% of the doubts.

It also means every POC should look unique. Because the perceived risk at the root of a customer’s indecision varies. (Yet most teams run the same process. They just swap datasets.)

The basic hypothesis is structured in a sentence like this:

If < this condition is true >, then < a reasonable conclusion >.

Then, your experiment should narrowly focus on proving out whether that condition is true, or false, and if led to the the conclusion. Which leads us into the last step of the framework.

(5) POCs Should End in Clear Go/No-Go Conditions

This is where you’ll use hypotheticals to talk about if/then scenarios with the buying team:

“If we’re able to show X, then we’ll want to move forward with Y."

"But if we only show Z, we’ll agree we don’t have enough evidence to rule out the main risks to moving forward.”

There are two key points here:

- “X” is your proof.

Something measurable shown during your POC, showing that the best case scenario is now the most likely scenario. Reducing risk, and raising your project’s Expected Value.

- “Y” are commercial terms.

You need to define the specifics of “Y” upfront. This prevents you from having to sell twice. Which the typical POC forces by delaying expansion discussions until after it's delivered.

Two more notes on defining “X.”

- Make sure the buying team drives how “X” is defined. Expectation Bias leads us to gather data that supports our beliefs, and deny the data that doesn’t.

- Once X is defined, ask, “If we hit this goal, and you’re NOT confident moving forward, why would that be?” Whatever they say is the actual risk your proof points should address.

Alright, with X and Y defined, you now have two possible scenarios:

- Go: The end condition under which these expansion terms kick in.

- No-Go: A bad or “just okay” result. Not enough to move forward.

All that’s left is to “hardwire” these go/no-go scenarios into your agreement. Which can be as simple as adding an attachment into your MSA with conditional language:

- If < X > is delivered by < date >, then < Y > terms are triggered.

- If < X > is not delivered by < date >, the agreement terminates.

The term “hardwiring” comes from the idea of creating permanent features inside a computer, by physically connecting circuits. So they can’t be altered by the software it’s running. So, if…

- Indecision strikes in the readout after a flawless POC

- A key contact or an executive suddenly leaves the org

- A current provider says, "50% off! Sign the renewal!"

… you’ve already helped your champion hardwire in their expansion upfront. It's now a permanent feature of their POC experience.

By the way, I was skeptical of this at first. Nervous it’d create too much friction to even get a POC going. But Jonathan, a very smart rep on a past team, pushed me on this.

He wanted this for his deals, and I’m so glad he did, because I discovered it's a gift for champions. You see, champions want your POCs to scale. They don’t want more negotiation, procurement, etc. The more time they spend on their day jobs with a solution, the better.

It may add in a few weeks into your evaluation and negotiation process upfront. But it’s well worth it, because afterwards:

- You have a single decision process to navigate.

- You can fully focus on hitting your POC goals.

- You’ll roll right into expansion after.

Here’s an editable POC worksheet, with step-by-step guidance for designing, delivering, and then debriefing your POC results:

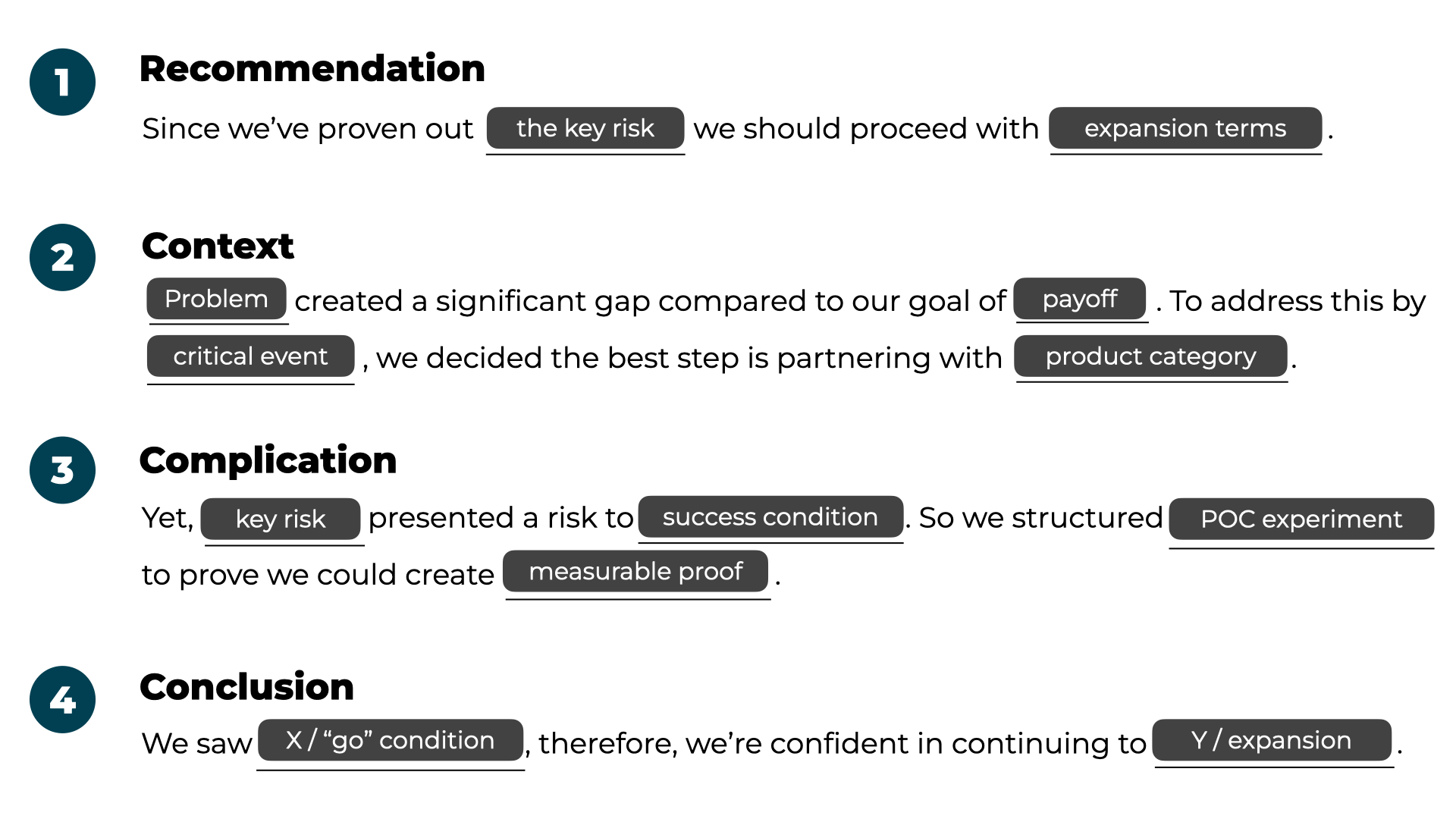

Use this Framework for Your POC Readout.

To be clear, hardwired expansion terms don’t mean your deal is guaranteed. You still need to:

- Partner with your account team to ensure you hit your “Go” condition.

- Hold a “readout.” An exec-level meeting to update everyone on progress.

The readout section of this POC framework looks like this:

Make sure your champions are heavily involved in creating and presenting this narrative.

Ideas are not independent of their messenger, so “renting” their reputation adds credibility to your message. Plus, they can help you navigate the committee’s objections and drama.

A Case Study in Digital Commerce

Here’s an example based on one of our past deals. We were working with the digital innovation team at a global cosmetics company.

A company whose primary sales channel before COVID-19 struck was retail. Customers would walk into a store and try on makeup to see how each product looked on their own, real-life skin.

Almost overnight, that was impossible. Retail sales plummeted across every market.

(For context, Fortune 500 innovation teams used our platform to find startup technologies they could quickly acquire, or integrate with. To launch new products or enter new markets faster and more cheaply than they could do in-house.)

Here’s how our readout framework looked:

1/ Recommendation:

Since we’ve proven [1] the time-to-market for a US-based, virtual lipstick try-on is roughly 3 months faster than an internal build, we should [2] expand platform access for project areas across the full portfolio of brands.

2/ Context:

[3] The drop in retail sales from COVID-19 has created a significant revenue gap compared to project earnings of [4] (redacted).

To address this by [5] the end of Q3, we decided the best course of action is engaging with [6] emerging AR/VR technologies that were previously vetted by VC partners.

3/ Complication:

Yet, [7] an early-stage company’s ability to safely integrate with and handle the volume of our eCommerce site presented a risk to [8] leveraging outside technology.

So we structured [9] a single-product test in the US market, to prove we could create [10] a faster time-to-market when introducing new tech to the customer experience.

4/ Conclusions:

We were able to [11] stand up a new customer experience in less than 8 weeks, therefore, we’re confident in continuing to [12] expand our approach across our product portfolio.

By the way, if you enjoyed this framework, you might like The Buyer Enablement Crash Course.

FAQ's on:

Why stop now?

You’re on a roll. Keep reading related write-up’s:

Draft with one click, go from DIY, to done-with-you AI

Get an executive-ready business case in seconds, built with your buyer's words and our AI.

Meet the sellers simplifying complex deals

Loved by top performers from 500+ companies with over $250M in closed-won revenue, across 19,900 deals managed with Fluint

Now getting more call transcripts into the tool so I can do more of that 1-click goodness.

The buying team literally skipped entire steps in the decision process after seeing our champion lay out the value for them.

Which is what Fluint lets me do: enable my champions, by making it easy for them to sell what matters to them and impacts their role.