How to Multithread & Navigate Dysfunctional Buying Groups in Enterprise Sales

TL;DR

Deals hanging by a single thread are risky. I know this. You know this. Everybody knows multithreading is a must.

Gong has good data to back this up, too: Closed-won deals involve 3X the number of people than lost deals.

There’s another thread to this conversation we often miss, however.

We spotlight multithreading as a must-do, while ignoring its shadow. The dark side and the dysfunction that’s always part of selling to large buying groups.

In other words, multithreading isn’t risk free either. There are wrong ways to multithread. Ways that create more deal risk like:

- Adding people to the buying group who can say no, but not yes.

- Nonlinear increases in your workload as communication compounds with each new person.

- Collective disresponsibility: the tendency to do less work as more people join a group.

So I’ll play both sides of the conversation in this writeup:

- Mr. Brightside: tactics to help you get and stay multithreaded with the right people.

- The Darkside: how to navigate dysfunction and manage negative group dynamics.

All through the lens of selling with champions. Because multithreading is where Buyer Enablement steps up like Michael Jordan in the NBA Finals.

Four Tactics That Guarantee You'll Multithread With the Best of 'Em

1/ Find a Common Thread to Tie Contacts Together

First, start by getting as clear as the waters in the Caribbean about how you help each stakeholder in the deal.

The phrase to help you here is, “Which means.”

Here's an example. Let’s say your product automates the process of tracking former users who recently changed jobs, and could champion your product for their new company.

“Which means” will help you find the common thread across:

Daily Users — > Directors & Champions —> Deciders & Executives

While stating the problem, you could say:

- Reps spend more time prospecting than managing pipeline, which means…

- Directors don’t have pipeline coverage to hit team quota, which means…

- The SVP will miss their goal of returning 4X each seller’s fully-loaded cost.

While framing the product’s value, you could say:

- Reps can engage warm leads who already know their value, which means…

- Directors always see a healthy pipeline coverage ratio, which means…

- The SVP hits every per-rep target in their financial model.

Now, your message ties everyone together.

2/ Handpick the Buying Team With Your Champions

Next, it’s time to work with your champions to buildout the buying team.

Assuming you have the 3 T’s of Multithreading in place, start weaving invitational language into your conversations to find and engage the right people:

Who else will this project impact, that hasn’t had a chance to weigh in yet?

Is there someone you turn to for advice on new projects or questions that are important to you?

That last question is particularly helpful, because it draws out contacts from the “shadow org chart,” and into your committee.

It captures the reality that influence isn't found in:

- Hierarchies

- Formal approvals

- Structured process

It's more often found in:

- Social capital

- Internal reputation

- Back-channeled convo's

Finding and adding high-influence (they can change internal direction) and high-incentive (they’re personally aligned with your deal) contacts to your committee is key.

3/ Proactively Multithread in Parallel to Your Champions

I’ve worked on multiple deals involving four or more different business units, where group calls started with introductions. Not for me. But for them.

So that people inside the same company could meet each other for the first time.

Champions can’t introduce you to people they don’t know. So it’s your job to enable them with outreach to new contacts who should be involved.

This type of outreach sounds like:

< New Contact >, I was hoping to include you in a conversation about < internal priority > with the < business unit > team next week. Would it make sense for you to weigh in on this?

If this doesn’t sound relevant for you right now, all good — < your business unit > tends to be closest to this topic at first, so I thought I’d reach out.

Even if that contact doesn’t take you up on the invitation, nobody was ever mad they were invited into the process early. It can only help, especially if they end up playing a role later on. They'll remember your invite.

4/ Engage Your Own Team to Mirror the Buying Team

Your access to a buyer's team often mirrors their access to your team:

- Bring an executive, meet their executive.

- Bring a technical team, meet their technical team.

- Collaborate with your team, multithread with theirs.

- Operate in your own silo, they will too.

Do the same thing you're asking your buyers to do. Show up with your team.

Language to kick this off might sound something like:

You mentioned needing to keep < Exec > posted, and it’s always helpful when we’re all on the same thread as questions or changes come up.

So, I can either write them a quick update before our next call CC’ing you and < Your Exec >, or, I can send it to you, so you can forward on the invite while CC’ing us.

What would you be more comfortable with?

When Multithreading Goes Wrong: 5 Risks to Avoid

1/ Don't Ignore the Difference Between Contact & Deal Stages

Basing your deal stage (and therefore, close probability) on a small subset of engaged contacts — like champions — instead of group behavior is a recipe for forecasting whiffs.

The reason is that buying committee members don’t move in sync. Their “contact stages” don’t line up with their “deal stage.”

If we simplify the reality of wandering buying processes into a handful of steps…

- Problem Aware

- Commitment to Act

- Forming an Approach

- Developing Requirements

- Selecting a Preferred Vendor, etc.

…and apply these steps to a buying committee, you'll get:

- A manager who's selecting a vendor.

- A VP who’s debating the right approach.

- A problem-aware operations team who's uncommitted.

- An executive who’s focused on an entirely different priority.

All inside a single deal record.

My champion's running pricing up the flagpole, so we’re at a 50% probability, is something I’ve said about many deals.

Which subsequently exploded.

Your champion may be all-in, but if the committee around them doesn't even agree on the problem, you're back at step one.

So here’s what you’ll want to do:

- Ground your forecast on where the “mass” of the buying group is.

- Determine where in the process they are based on these behaviors.

- Move your deals backwards as needed to line up with 1 & 2 here. (This will drive your leadership nuts, but it's better to be accurate than commit to what won't close.)

2/ Don't Leave Champions to Handle Group Conflict Alone

If your sale feels too smooth, there’s a good chance your champions are sanding down points of friction on their own, to keep your deal gliding along.

The reality is someone always has a different opinion. You don’t want to leave champions to find and disarm those counterpoints alone.

Instead, you want to ask questions that invite yourself into the consensus-building process. Encourage dissent, and help the buying committee find consensus by saying:

Seems like everything’s moving forward smoothly, so I’m wondering, is there someone on your team who you think might be willing to disagree with us, so we can be sure we have a good fit?

The key to this phrasing is “willing to disagree.”

You’re asking for a nomination. Someone who would be so kind as to play the role of devil’s advocate. Which is a practice I’ve used with my own internal teams. If we’re launching a new project, we ask someone to poke holes in the plan to make sure it stays on track.

Guess who ends up filling the role? The strongest critic.

If you're feeling some dissent already, call this out more directly:

It doesn’t seem like < contact > fully agrees with this point. Is there something you feel we might have missed considering?

The idea here is that there’s never a single “decision maker,” because of all the people who can say no.

While there may be one “economic buyer,” everyone in the committee who can say "no" is a decision maker, too.

“No,” is a pretty clear decision just the same as “yes.” So you as the committee grows, bring dissent into the open. It’s exists whether you’re part of addressing it, or not.

3/ Stop the Sprawl: Don't Let the Buying Team Keep Expanding

Related to that last point, you want to keep the buying team narrow. If more people get involved than you truly need, not only are you increasing deal risk and indecision, you're compounding your workload.

Seth Godin describes how the volume of communications and approvals compounds with each new person on the committee:

Handshake Overhead is the result of the simple law of more people: n*(n – 1)/2. Two people need one handshake to be introduced. On the other hand, 10 people need 45 handshakes. More people involves more meetings, more approvals, more coordination.

Which means you can quickly devolve into a mini-communications-department-of-one. Working reactively instead of designing the flow of internal communications.

With a massive workload that's way too much for one person to manage — even with a group of committed champions.

For example, if you apply the "Handshake Overhead" formula to the number of people on the buying committee, multiplied by the number of deals in your pipeline, here's your reality:

4/ Don’t Let These Cognitive Biases Crush Your Deal

There are two errors in the way we think that can sneak up on your champions:

- The False Consensus Effect.

Which leads people to overestimate just how much others actually agree with them.

- The Transparency Illusion.

Which causes us to believe that others know the full scope of what we’re thinking.

Champions fall prey to both when they believe the rest of the buying team is on the same page with them, when in fact, others may not understand why they believe in the deal so strongly.

A question like this can help pull your champion out of that illusion:

It seems like you want others to want this more than they do. If that’s a fair characterization, how do you think we could help them see what you see?

Or, you can try labeling someone who seemed to be scrolling LinkedIn during your last call:

Seems like < contact > could be happy with any outcome to our conversations. Whether we move forward, or don’t. Is there something missing from this project, that you think means this isn’t a must-have for them?

This is particularly key if who you’re calling out is a “High Influence” contact.

5/ Don’t Multithread When You Hear These Two Things

There are a handful of occasions when multithreading is counterproductive.

One case is when you see a buyer triangulating themself. Giving someone a clear and direct “no” is uncomfortable. So they’ll deflect to their team:

Sorry it’s taken a while to reply. The rest of our team just hasn’t been very interested.

This means you need to ask a question, to separate their interest from their team’s:

Gotcha. How are you feeling about that? Were you wanting your team to want this too? It’d be understandable if you weren’t.

Asking helps you determine if there’s a challenge with the committee — or this one contact.

Another occasion is discussing pricing. Holding a group call to discuss pricing is rarely the way to go. The reason?

People react how they believe they’re supposed to react in group settings.

They're less likely to share what they truly think. “Will I look like a pushover if I don’t push back on this?” Besides, you don’t need group approval on price. Just to finalize your scope. The first topic depends on budgets. The second depends on needs.

Since they’re separate topics, make them separate meetings.

You’ll have a more transparent and productive conversation this way.

An example here is:

< Champion >, I’m thinking we have a good handle on the full group’s needs now. It was also helpful to hear < Decider’s > goal on keeping your recurring spend low.

I rolled both of these inputs into a set of contract options for us to look at. Could the three of us put our heads together on feedback this week?

Closing Thoughts

- Creating the MVC: Minimally Viable Committee

If you find that the buying committee keeps expanding, it’s a sign of dysfunction. When we’re not confident, we let others decide for us. This shifts the blame, because if I let you make the call, and things go south, then ultimately, it’s your fault. Not mine.

In this case, you’re too multithreaded. Instead, you want to maintain the MVC. Just enough people to confirm the problem, create a use case, and clear the contract.

- Reselling the Problem & Priorities

Lastly, if you’re still hitting unresolved conflict or indecision, you might need to step back to see if something’s changed about the problem or its level of priority.

In complex deal cycles that stretch up to a year or longer, anything can happen. For example, you’re more likely to hit turbulent air and get rerouted while flying from London to Los Angeles, than from Los Angeles to San Francisco.

FAQ's on:

Why stop now?

You’re on a roll. Keep reading related write-up’s:

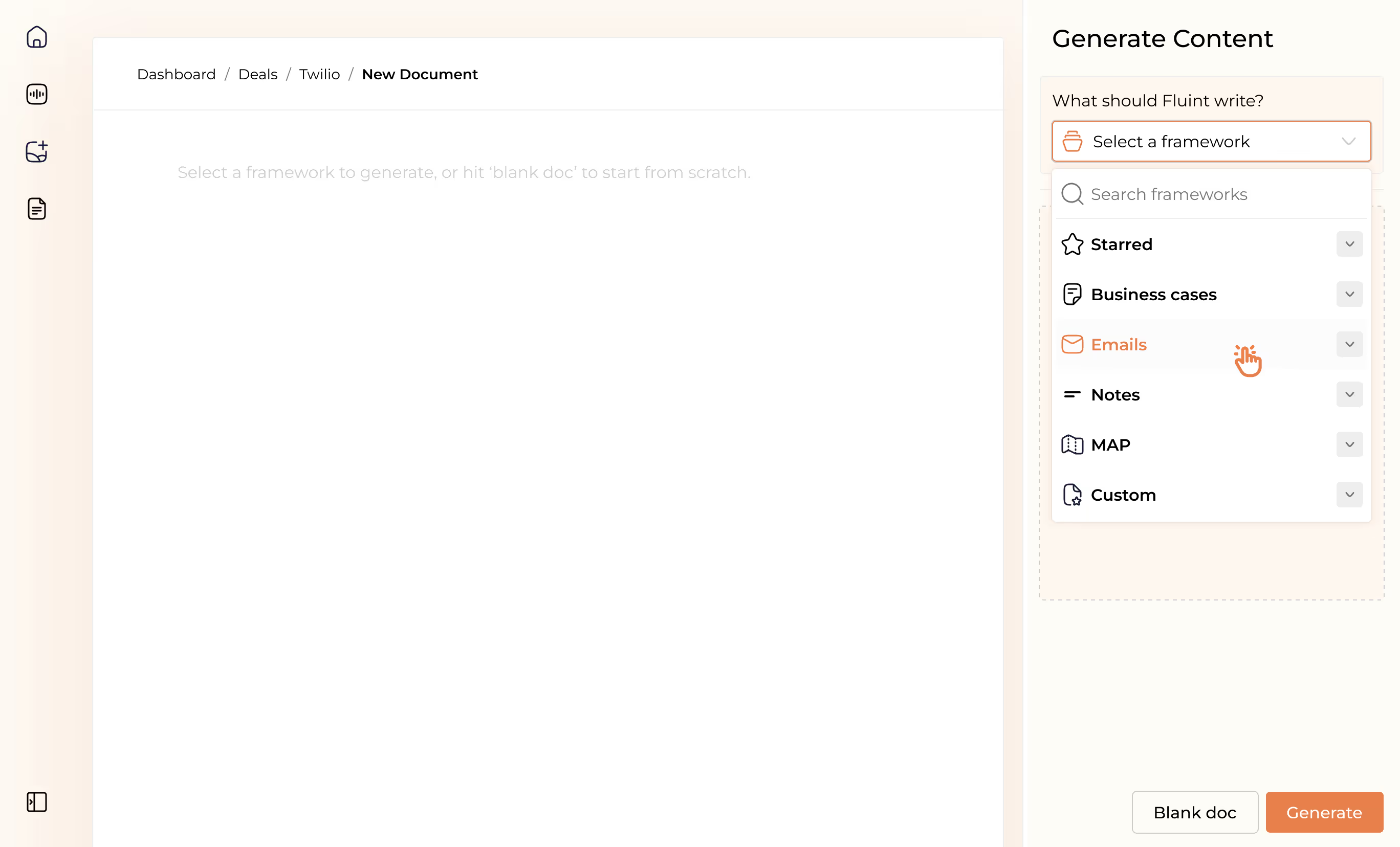

Draft with one click, go from DIY, to done-with-you AI

Get an executive-ready business case in seconds, built with your buyer's words and our AI.

Meet the sellers simplifying complex deals

Loved by top performers from 500+ companies with over $250M in closed-won revenue, across 19,900 deals managed with Fluint

Now getting more call transcripts into the tool so I can do more of that 1-click goodness.

The buying team literally skipped entire steps in the decision process after seeing our champion lay out the value for them.

Which is what Fluint lets me do: enable my champions, by making it easy for them to sell what matters to them and impacts their role.