The Change Equation: A Framework to Keep Deals from Falling Apart

TL;DR

I’ve been changing the settings on our office building’s coffee machine for the last few weeks. The nerd in me couldn’t resist a little experiment.

When you pick your drink — espresso, americano, etc. — it asks how strong you'd like it brewed. There are 5 levels. I move the setting from 1 (very weak) to 5 (very strong) every few days.

Guess what?

People always brew their coffee on whatever level I set it to. They don’t change it. Even if they’re drinking hot bean water, or motor oil.

The point?

People don’t like change. They stay on the path they’re put on. Even if it’s less than desirable. Which is why your deals will fall apart despite building up a logical, solid financial case.

And the thing is, our resistance to change isn’t rational. It’s a type of mental barrier we build.

Even if we’d prefer life after the change.

I mean, nobody prefers drinking stained water over coffee. But they drink it anyway in my office.

Nobody prefers manual and frustrating workflows. But they live with them in their office.

Here’s the good news:

You can design a decision process that makes even large-scale change feel as inevitable as the people in my office drinking gross coffee this week.

You can shift a buying team’s direction in a way they’ll just keep walking forward down the new path. Here’s how. By shaping your deals around The Change Equation.

The Change Equation: A Framework for Enterprise Sellers

The product teams I’ve been part of thought about change with a simple equation:

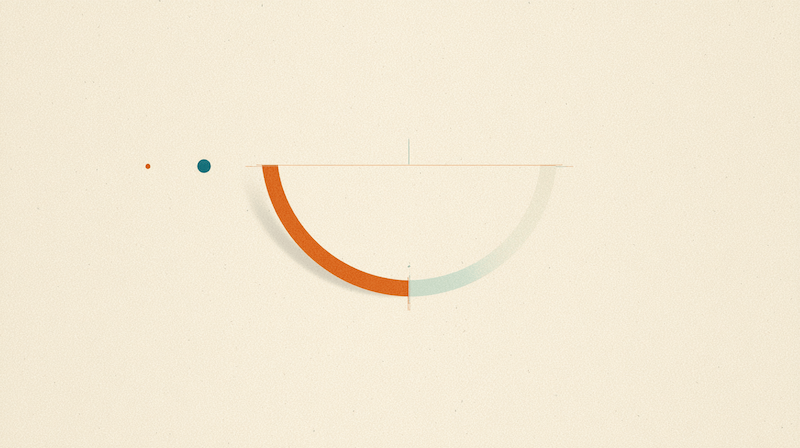

Change = [Push of Pain + Pull of Product] > [Current Habits + Future Anxiety] x 10

The basic idea is you need to show customers:

- Costly, unbearable problems caused by their current state.

- Plus compelling features that can enable better outcomes.

- That are an order of magnitude larger than resisting forces.

It was a good starting point. But recently, I came across “The Formula for Change,” created by researchers David Gleicher and Kathie Dannemiller, to study organizational change.

Here’s the short version of equation:

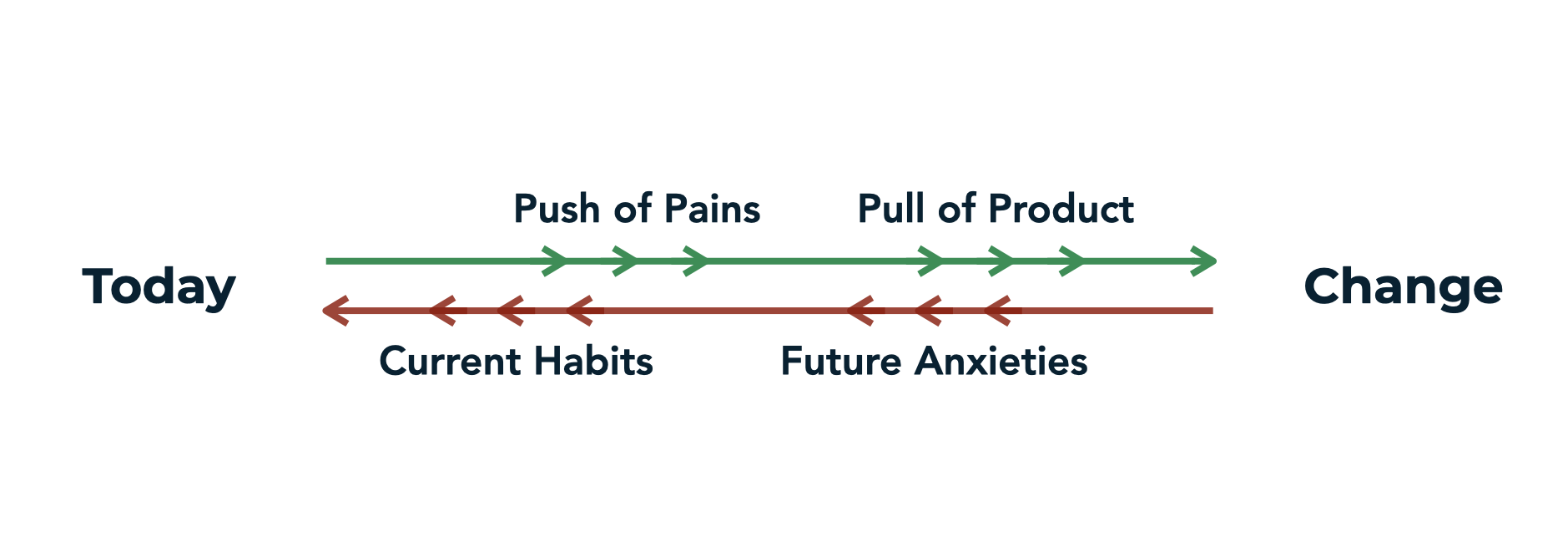

C = D x V x FS > R

Each of these variables stands for:

- D = Dissatisfaction with the current state.

- V = Vision of what’s possible.

- FS = First concrete steps to move towards the vision.

- R = Resistance to change

When the product of the first 3 variables are greater than resistance, change happens.

Now, notice how the equation:

- Relies on each variable. Since they’re multiplied by each other, if any of them are incomplete or missing (so they’re equal to 0), resistance wins.

- Directly aligns with The Discovery Roadmap. The equation’s drivers and the Roadmap’s framework are the same. Problem (D), Process (FS), Payoff (V).

Here’s what this means for you in the context of an enterprise deal.

Resistance Isn't Logical. That’s Why It’s Powerful.

Change resistance isn’t about reality. It’s about the stories we tell ourselves. The mental barriers we build to avoid discomfort, maintain control, and eliminate fear.

That’s why it’s so hard to overcome.

It's like trying to win when somebody else makes up their own rules. If we’re playing soccer (football, outside the US), and I say I get to pick up the ball and run through you like it’s a game of rugby, I’ll win. Because I’m not playing by any sort of logic.

This is exactly what your buyers get to do. They make the rules.

So activities like presenting a massive ROI or a better feature set don’t matter on their own.

You’re playing by logic in that moment, but as advertising legend Rory Sutherland says:

The human mind does not run on logic any more than a horse runs on petrol.

The question, then, is how do you play an illogical game and win? Can you tip the balance of the change equation in your favor?

Yes, in short. It’s like Sutherland later says in his book Alchemy:

Our conscious mind tries hard to preserve the illusion that it deliberately chose every action you have ever taken; in reality, in many of these decisions it was a bystander at best, and much of the time it did not even notice the decision being made.

So here’s how to design the buying experience around the next 3 drivers. So that the decision to change is barely noticeable:

- (D) Build an unbearable level of dissatisfaction with the current state.

- (V) Paint a clear and compelling vision of the future together.

- (FS) Outline specific and concrete steps to move toward the vision.

(D) How to build an unbearable level of dissatisfaction with the current state.

The current state becomes unbearable when problems are specific, highlighted, and prioritized.

If they’re vague, hidden, or ignored, resistance wins.

1/ Make the problem specific, not vague.

”Our lead capture isn’t optimized, so we’re missing out on leads,” is pretty weak tea.

The impact of that statement overly diluted.

By contrast, a strong problem statement is specific. It uses customer data to show costs and consequences. (Read more about building statements like this, here.)

Otherwise, here’s how your sales cycle will play out:

2/ Make the problem highlighted, not hidden.

Ever heard of the Ostrich Effect?

We ignore bad situations when we’re personally accountable for them. Because admitting there’s a problem is often way more painful than living with the consequences.

So once you’ve built that problem statement, make sure your champions share it. Over, and over, and over again. While tying the cause to the status quo.

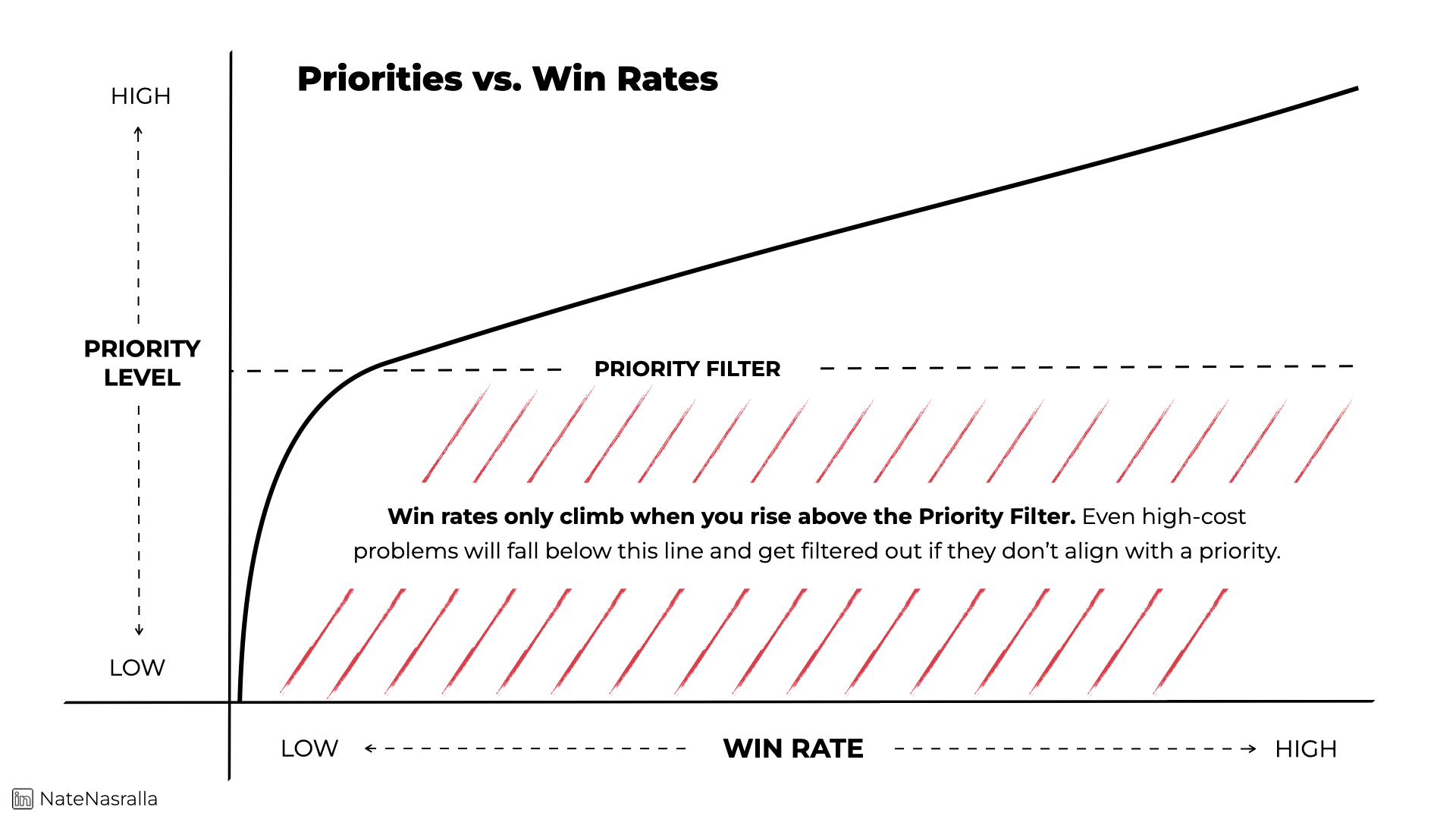

3/ Tap into priorities to make sure you’re not ignored.

If you recall from this write-up, issues that aren’t blocking a leader’s priorities are seen as distractions — not true problems.

Which is why there’s a graveyard of dead deals, never to be resurrected, below the priority filter:

(V) Paint a clear, compelling vision of the future together.

You’ll add weight to this lever when the buying team feels clarity, consensus, and confidence.

This value drops if your messaging is diluted and murky.

1/ Craft a compelling narrative.

Stacking up a series of case studies and branded decks in a microsite won’t compel executives to embrace change. It’ll just reinforce you’re there to talk product.

Instead, you need to connect your narrative to an existing narrative inside the target account.

If your narrative will make the...

- Headline of a press release

- First minutes of an earnings call

- Agenda of a board meeting

...you’re on the right track.

Or, even better, as my friend Brandon Fluharty says, the executive’s personal legacy.

2/ Clarify the payoff. Don’t leave it looking murky.

Using a “current vs. future state” comparison can be powerful. But most reps end up creating more sales resistance with it. The problem is how they’re applying the practice:

- They contrast current vs. future process

- Not current vs. future outcomes

That's an issue because:

- Contrasting outcomes is a measure of value.

- Contrasting process is a measure of change.

And remember, buyers don’t like change. It’s risky and hard. So calling out how much process change is needed isn’t very helpful.

The way to fix this is:

- Contrast current vs. future outcomes.

- Confirm that change is wanted / a priority.

- Find a small, specific scenario in their process.

- Show current → future change for this scenario only.

Now, there's a clear vision for the future with a bite-sized example of how you'll get them there.

Here's an example of steps 3 - 4 above:

🔴 Don’t say:

Excel spreadsheets are prone to errors and take time with manual data entry. We'll replace those spreadsheets to automate all of your EOQ forecasting.

🟢 Instead, say:

Forecasting key accounts is subjective, and drastically swings the EOQ forecast. Let's start by comparing a machine-generated forecast to Excel's, for your top 20 key accounts.

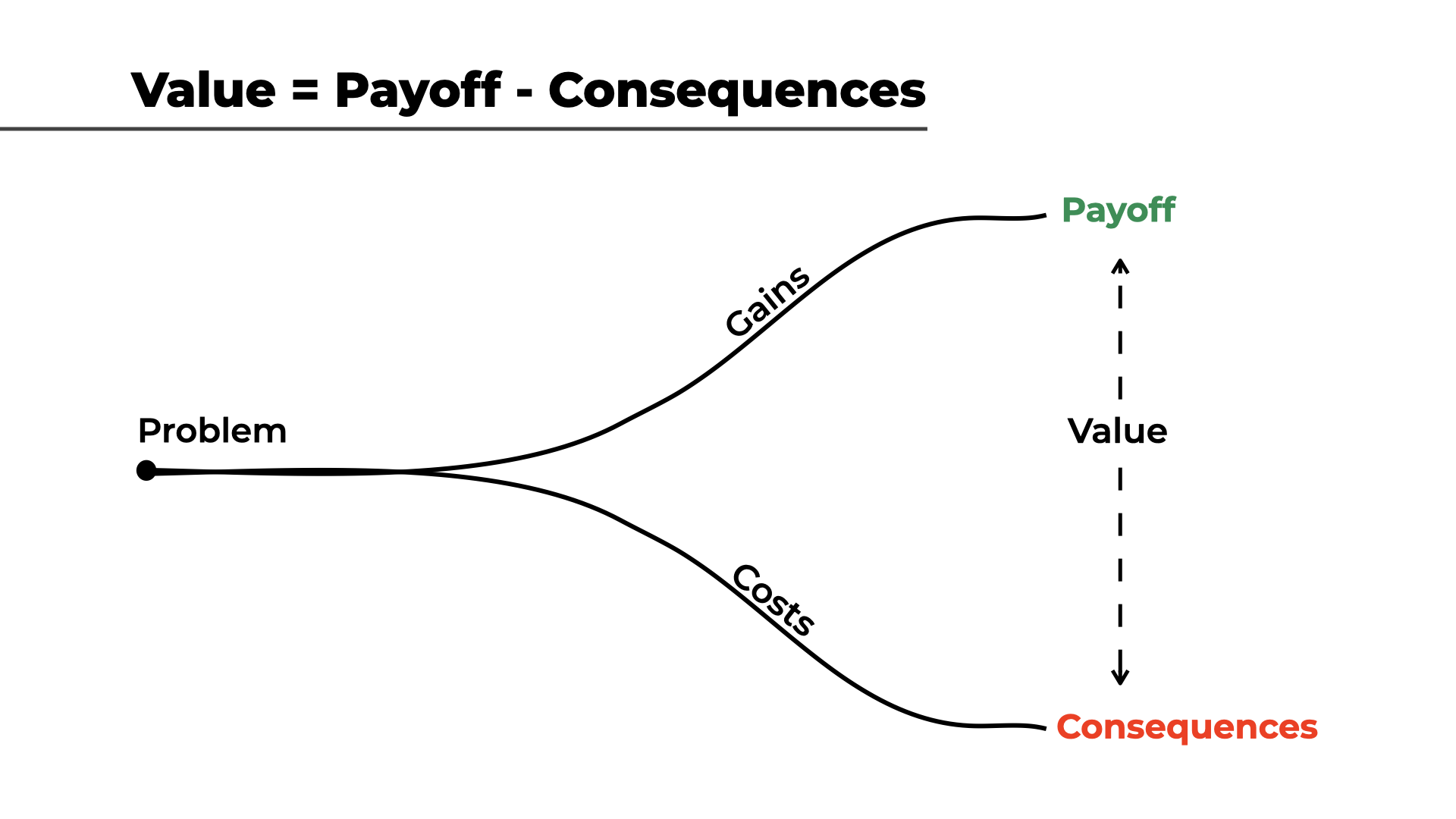

In other words, value = cost of the current state (-) payoff of the future state.

So once you’ve quantified loss ("D" in the change equation), use those same metrics and flip them upside down to quantify gain.

3/ Deconflict competing incentives.

Every contact inside a large buying group has a different set of personal metrics and projects. So your message has to thread the needle between everyone’s WIFM (What’s in it for me?).

As Upton Sinclair said:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when [he believes] his salary depends on his not understanding it.

(FS) Outline specific, concrete steps to move toward the vision.

The scales tip towards change when there’s a specific and approachable path to move from the problem to the payoff. Keep in mind the change equation dips towards resistance when:

1/ There is no path.

If your buyers are wandering around a complex, non-linear buying process without any guidance, they’ll just stop moving forward. Which is why:

- Good reps script the path with a mutual action plan.

- Great reps show a specific onboarding and rollout plan.

For example, in the back half of our sales cycles, we’d share the rollout plans from similar customers (e.g. we showed Allstate how we ensured that State Farm was successful).

That brings a strong feeling of, “If it worked them, this should work for us too.”

2/ The decision feels like a first-time not a repeat choice.

When you can show congruity between...

- The decision you’re asking someone to make today

- The decisions they’ve already made in the past

...you’ll decrease their resistance to change.

The way you’ll do this is by positioning the path forward as a “Hyperlinked Decision.”

That’s when a new buying decision references a previously-executed decision, made by the same person, with a positive outcome. It lowers the perceived decision risk by “embedding” itself within a natural series of escalating commitments.

New decisions bring way more stress, uncertainty, fears and doubt.

Making a second or third decision that builds on what’s already been started is far easier. Some example phrasing you can use here is:

Even if it was manual, have you tried anything similar to this in the past? How did that go?

For example, let's say you’re in the data management space. Moving someone to a “graph database” may feel like a massive change. But if you discover the answer here is...

Yeah, we manually pull 5 - 10 different files from our SQL database, and them match them up using lookups inside Excel based on how we know they relate to each other.

...then, you’re hyperlinking the choice to move to a graph database to their existing behaviors.

3/ You left the parking brake on.

My favorite line from the book The Catalyst is:

Sometimes change doesn’t require more horsepower. Sometimes, we just need to unlock the parking brake.

Parking brakes are why buying teams don't move toward their vision, away from the status quo.

They’re specific blockers, often rooted in unique factors like:

- The need to feed internal drama to feel needed.

- Past data or privacy breaches leading to more intense security reviews.

- Failed projects that left permanent scars on someone’s internal reputation.

So if your deal is creeping along slowly, try asking, "Why haven't they changed already?"

Find the specific parking brake that’s left on.

4/ You didn’t bring others along for the ride.

Gokul Rajaram, the executive in charge of Square’s Caviar restaurant delivery service, shared the perfect story about taking first steps without ensuring the right people are on board:

I remember one instance that had to do with the change in policy for how engineers wrote unit tests for software. The decision maker, an engineering lead, had consulted with several of his fellow engineering leads and felt comfortable with his decision.

Then he sent an email with the policy update decision to all of Square’s engineers. Within 30 minutes, a dozen people replied, many of them disagreeing vehemently with the decision.

To his credit, the lead took ownership. He froze the decision and invited every engineer at Square who agreed or disagreed with the decision to meet with him over the next week. I think a dozen people took him up on it and went to his office hours. A week later, he sent his new decision out by email.

Guess what? It was exactly the same decision as the last time. But this time, nobody complained. Why? Because they all had been listened to.

So the question is, who in your deals needs to feel heard, but doesn’t?

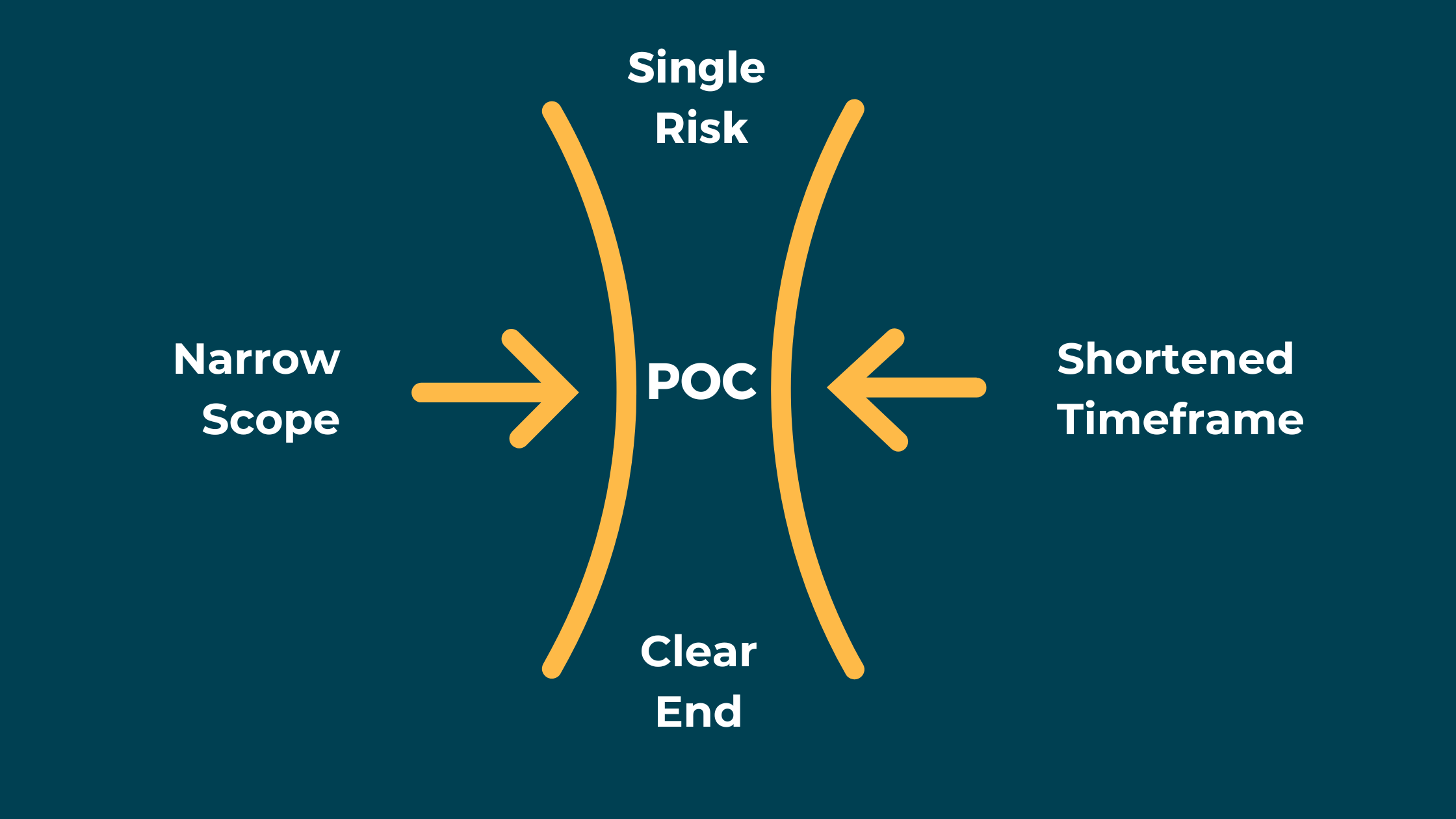

5/ The path feels far too risky.

Like the idea of a parking brake, fear and doubt can typically be broken down to a specific cause. Which is where executing a hardwired POC can take risk off the table — without losing any deal momentum.

6/ There’s no payoff in the process.

Enterprise projects take time. Evaluation through implementation can be 2+ years. That was especially true when I sold to Fortune 500 innovation teams. They worked on 3+ year timelines.

Which conflicts with our brain’s Hyperbolic Discounting:

We choose immediate rewards that are smaller, over larger rewards that come later.

Which is why the process you walk your buyers through has to payoff in the short-term, by helping them get their job done today.

Here's an example email framework to help you do exactly that.

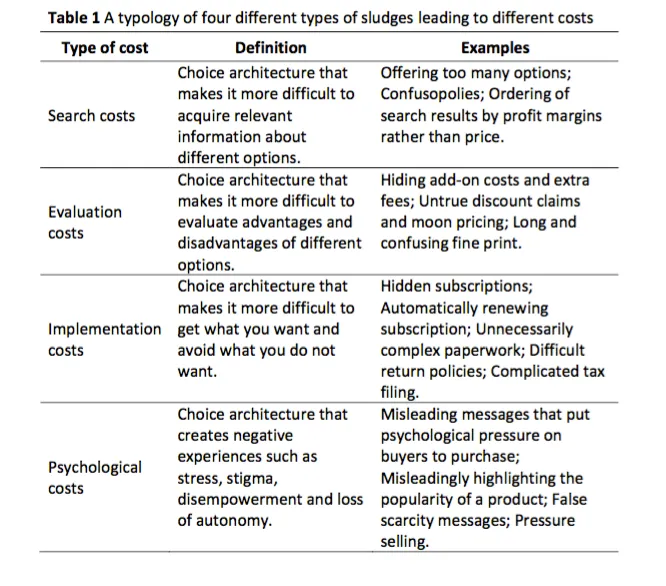

7/ There’s too much “sludge” in the process.

Sludge is process friction that prevents people from moving forward to get what they want. This article and chart breaks down four different types of “sludge” that add to change resistance:

Any of these examples sound familiar?

Offering too many options? Hidden fees? Complex paperwork? False scarcity?

Yeah. Unfortunately, I think a lot of buyers would say they're all too familiar.

But since you just read 2,100 words on designing your deals with your buyer's fears and anxieties in mind, I have full confidence they won't be saying that about you.

FAQ's on:

Why stop now?

You’re on a roll. Keep reading related write-up’s:

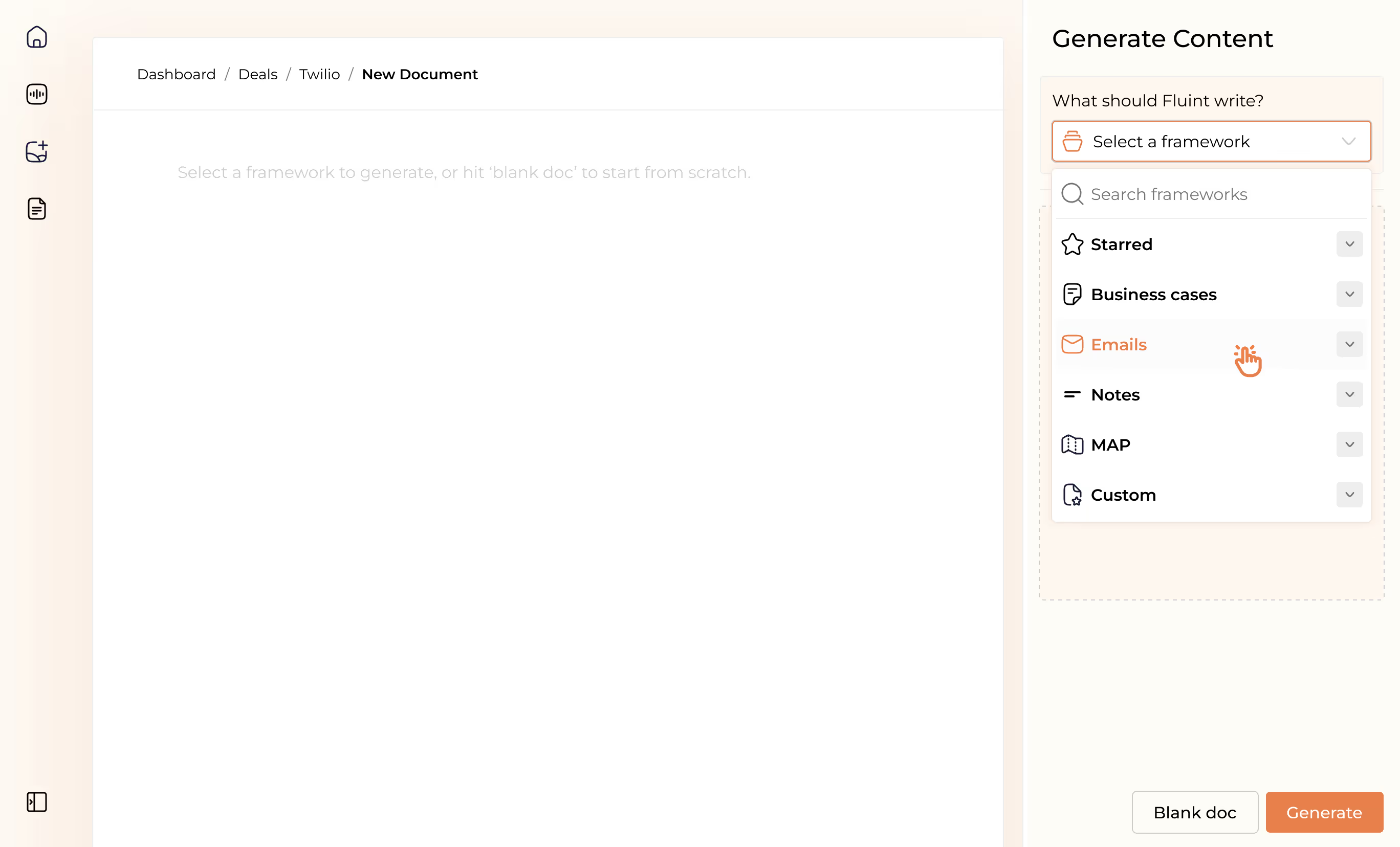

Draft with one click, go from DIY, to done-with-you AI

Get an executive-ready business case in seconds, built with your buyer's words and our AI.

Meet the sellers simplifying complex deals

Loved by top performers from 500+ companies with over $250M in closed-won revenue, across 19,900 deals managed with Fluint

Now getting more call transcripts into the tool so I can do more of that 1-click goodness.

The buying team literally skipped entire steps in the decision process after seeing our champion lay out the value for them.

Which is what Fluint lets me do: enable my champions, by making it easy for them to sell what matters to them and impacts their role.